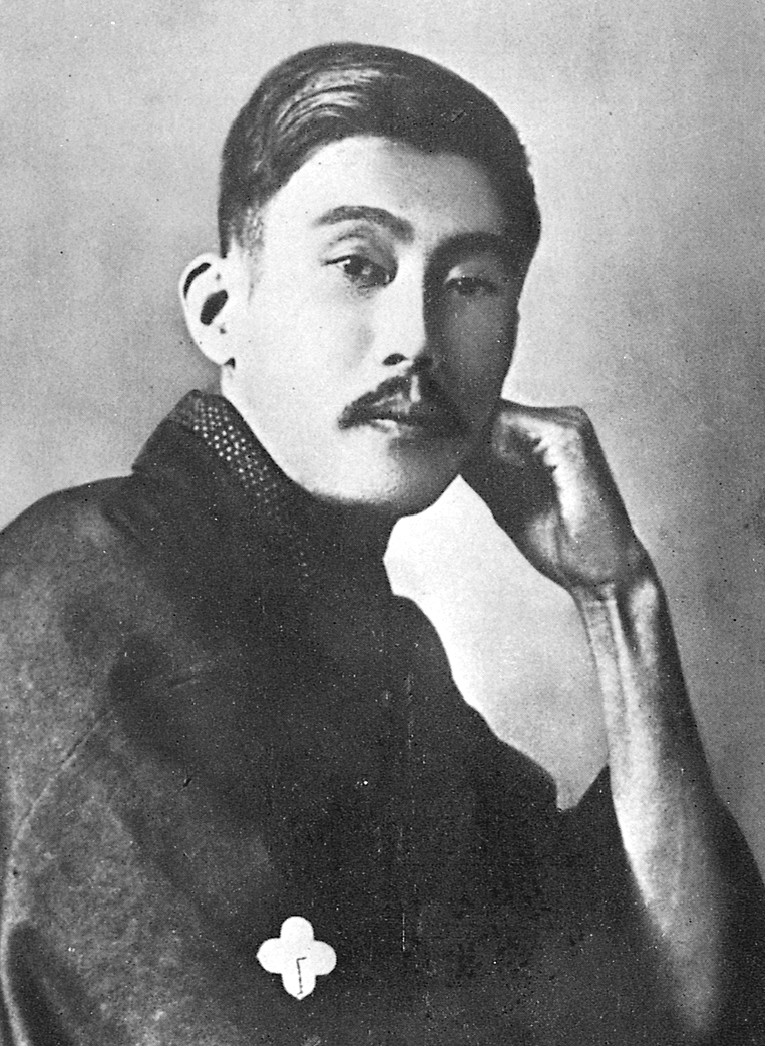

Another title published from London Magazine Editions, Three Contemporary Japanese Poets appeared in 1972, focusing on poems of the three poets, Anzai Hitoshi, Shiraishi Kazuko and Tanikawa Shuntaro, the translations are by Graeme Wilson and Atsumi Ikuko. Both Shiraishi and Tanikawa have several books in English translation, the latest by Tanikawa is the collection The Art of Being Alone, a selection of poems translated by Takako Lento that span the years 1952-2009, published as part of Cornell University's East Asia Series, a book that I've earmarked to be read in the new year. Takako Lento has also recently translated a selection of poems by Heiichi Sugiyama for Poetry International Web, Last Words and Water being two which seem to remain with me at the moment. Canadian born Shiraishi Kazuko has appeared in translation, notably in the three collections published by New Directions, Seasons of Sacred Lust, Let Those Who Appear, and most recently, My Floating Mother, City, although in this volume only ten pages are given in examining her background and poems, it still remains an informative piece, the poems are interspersed through a brief bibliography and biography, featuring poems from her first collection The Town Where Eggs Are Falling. Anzai Hitoshi is explored a little more indepthly though, Anzai is a poet not much translated in English, the selection here includes twenty translated poems and an informative piece on Anzai, born 1919 in Fukuoka Prefecture, first trained as a teacher but dropped these studies to become an editor for poetry magazine Sanga, he spent some time editing at the Asahi Shimbun. Interested in classical Japanese Literature and French poetry; Francois Villon and Jacques Prevert in particular, although his poetry breaks from traditional styles, Wilson observes though that he hasn't taken the route of the then very contemporary Concrete Poets, which you get the impression that maybe Wilson was none too impressed with. Anzai's poetry captures the fleeting moment, in the poem Snow, Anzai presents a picture of mourning, the poem ends with a reminder that even after people and things have passed, to those that remain fate remains an undecided factor in the equation. Although the traditional seems to be at the periphery of Anzai's poems much of the language used in them reflects the modern, as in the thematically linked poem Disused Railway Station and in the the poem My Eyes, which envisions aspects of the contemporary world viewed around but ends with a glance at the approach and passing of time.

My eyes are the driving-mirror

In the cab of an all-night truck:

They watch time's headlights

Crowding up behind me.

The thirteen poems by Shunatro Tanikawa include the seven part poem A Syllable of Seeing (Portraits of Womankind), the bibliographical and biographical piece describes Tanikawa's upbringing within an intellectual environment, his father was the philosopher Tanikawa Tetsuzo which instilled an aversion to academical life. As a young poet he was sponsored by the poet Miyoshi Tatsuji, and Wilson looks at the period when he wrote his first two books Solitude of Two Million Years (1952) and 62 Sonnets and his joining of poetry group Kai(Oar). The bibliography in this piece is really good including descriptive passages on Tanikawa's, Ehon, (Picture Book), from 1956, and his book from 1968, Tabi (Travel), some from Tabi are included here. A Syllabary of Seeing, (Portraits of Womankind) contains seven syllable each focusing on different women, the first is of a woman, perhaps a first love, the poem subtly captures the first moments of the recognition of attraction, the second which begins by an observation of a grand- mother's eyes and then the following stanzas explore landscapes which although at a first reading don't appear to be linked, the poem goes onto form a cohesive image of slight decay. The third starts by examining a past lover, the poem then goes on to explore an emotional world that is both discarded but at the same time has a distant familiarity to it. The fourth is a poem which has an air of a measured reconciliation contrasted with images of a mixture of emotions that have either escaped or are unattained. The fifth begins with an observation of a daughter and is a meditation on a world of possibilities, the sixth is a retrospective glance of the narrator's mother, and memories from childhood, reaching the seventh syllable we discover that the narrator of the syllables is that of a woman, which by turns forces the reader to reconsider the perspectives of the preceding pieces, the last syllable is a self portrait. This is an interesting introductory book to these three very different poets which will be of interest to those both familiar and new to the poets it looks at.

A SYLLABARY OF SEEING

(Portraits of Womankind)

THE SECOND SYLLABLE

I look at a woman,

My mother's mother. I look at the huge,

Serenely black

Eyes of the gentle

Reptiles whom the earth wiped out

Millennia back.

I look at a sinking

Sailing-dinghy whose jib-sail flickers

In the running tide.

At a line of beach-guards

Drawn up stiff, like singing skeletons,

Side by side.

I look at a tilled

But stony hill. To that stoniness

My eyes return,

To a hillside seared

With the marks of flame, with the ulceration

Of after-burn.

At cheeks inflamed

By imminent flesh, by the body's mantle

About to fall.

And I look at Medusa's

Head observed in the hustle and bustle

Of carnival.